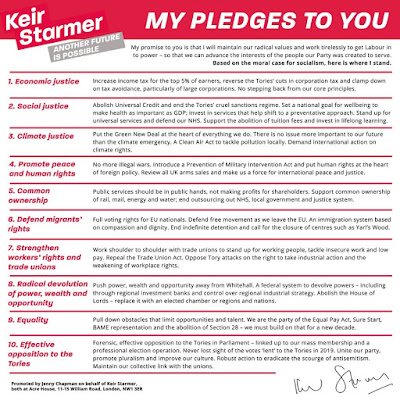

The 10 pledges made by Keir Starmer on his way to victory in the Labour leadership election planted his campaign firmly in the ground marked by the 2017 general election manifesto that almost put Corbyn's Labour into government. But six months on, questions are increasingly being asked about whether he intends to stand by them. On both the left and right wings of the party and among some commentators there is a growing belief that the pledges were nothing but a ruse to lure former Corbyn supporters away from his chosen successor Rebecca Long-Bailey, and having served their purpose are now in the process of being quietly dropped to make way for a return to Blair-style centrism.

But is this belief actually true? Approaching this question as a very forensic lawyer might do, let's first consider the case for the prosecution.

The belief on the Labour right and among centrist pundits that Starmer is their man is well summed up by Andrew Rawnsley's recent column on his conference speech. His article is saturated with glee at the direction he perceives Starmer to be travelling in, and in particular he interprets the under-new-leadership message to "heavily imply that he no longer feels tied to the promises he once made to stay faithful to the Corbynite prospectus".

On the left this triumphalism is noted along with many of Starmer's actions since becoming leader, from removing Corbyn allies from the front benches while bringing in his biggest critics from the cold, abstaining on issues where Corbyn would have taken a stand, refusing to back protestors, and above all sacking Long-Bailey.

It is not a large step from there to seeing it as self-evident that Starmer's campaign pledges, and in turn his assertion that Labour should not "oversteer" from Corbyn's agenda, were a con trick.

The case for the defence has to start from the assumption that Starmer is sincere about the pledges. Under this lens, the criticisms become a misread of what Starmer has been doing with his first months in office. From this standpoint his actions could be seen as simply a fulfilment of pledge 10, i.e. effectively opposing the Tories (no matter how unfair this is to Corbyn's time as leader). It's not a surprise, for example, that he did not rate many of Corbyn's allies as shadow cabinet material, and he clearly wants to pick and choose his battles, avoiding anything that might give the Tories an opportunity to paint him as an unpatriotic, metropolitan Remainer type.

The defence must acknowledge that his tone since winning has certainly all been about drawing a line under the Corbyn years. But while Rawnsley reads into Starmer's conference speech a plan to forsake the pledges, there is actually

nothing in the speech itself to justify the idea. None of his actions or words, in fact, infringe on the pledges at all, and indeed Starmer

recommitted to them only last week.

From this point of view the "under new leadership" messaging of Starmer's first six months in office is the first step in getting as wide as possible a coalition behind his policy agenda. And he'll reach his final goal when commentators like Rawnsley forget that they were ever against them in the first place. Deeply unfair to Corbyn's legacy though it is, Starmer clearly regards a clean slate as part of fulfilling his tenth pledge, and

the polls back him up.

So who is right? Both the prosecution and defence cases clearly have some merit, but in my view it is the prosecution that have the most awkward questions to answer.

First, why did Starmer bother to make the pledges in the first place if he did not intend to honour them? He was already

comfortably in the lead well before he put them to paper. He could have kept his pitch vague and still strolled home, so why did he feel the need to set them out in all their meandering, oddly-edited detail?

Second, we know by now that Starmer likes to plot routes from position A to target B as methodically as possible, leaving no hostages to fortune. Take his Knightmare-style journey to the leadership, which until fairly recently was hardly inevitable, causing many other candidates to slip up before they even reached the campaign. And then there is his successful softly-softly, step-by-step approach to changing Labour policy on Brexit (for better or worse, according to taste). Surely then it is out of character to make a long series of pledges that could be hung around his neck for the rest of his time as leader unless he was sincere about standing by them?

The lack of good answers to these questions does not prove that Starmer won't drop the pledges eventually, of course. He would hardly be the first politician to

cynically drop a high profile pledge on going into government, after all. And he will have pretexts to do so: from the huge hole in the public finances caused by the pandemic to the inevitable compromises necessary in a hypothetical Labour/SNP government.

But while it is certainly premature to declare Starmer "not guilty", to my mind the case for the prosecution is fairly weak as things stand. A more likely explanation for his words and deeds to date is that it is his strategy to get the ideas of Labour circa 2017 a fresh hearing under the guise of an establishment-friendly leadership. Whether that strategy is a good one or not I have no idea, but if he does manage to pull it off, there is at least a chance that those ideas could actually be implemented without the inevitable gigantic backlash that would have occurred had Corbyn won three years ago.

Comments

Post a Comment